Modern Portfolio Theory Revisited: Optimisation, Correlation, and Fragility

Seventy years after Harry Markowitz’s groundbreaking 1952 paper, the financial world is moving from "theoretical optimality" to "operational robustness." This article explores the mathematical elegance of the original Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), why its reliance on stable correlations fails during market crashes, and how researchers in 2024 are using convex optimization to build portfolios that can actually survive the real world.

Yanhel AHO GLELE

1/9/20264 min read

Introduction :

In 1952, Harry Markowitz published a 14-page paper that would fundamentally transform finance from a qualitative art into a rigorous mathematical science. Before Markowitz, investors sought the "best" stocks in isolation; after him, the focus shifted to how those stocks interacted within a collective. This was the birth of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and the industry's only "free lunch": diversification.

By quantifying risk as variance and return as the mean, Markowitz provided a roadmap for the Efficient Frontier—a theoretical boundary where an investor achieves the maximum possible return for every unit of risk.

However, seventy years of market turbulence have exposed a hidden fragility in this elegant math. From the "Black Monday" of 1987 to the global liquidity shocks of 2008 and 2020, practitioners have learned that the "free lunch" often disappears exactly when it is needed most.

Today, we are witnessing a necessary evolution. By revisiting Markowitz’s foundations through the lens of modern research—specifically the robust, convex optimization techniques proposed by researchers like Stephen Boyd (2024)—we can bridge the gap between 1950s theory and the brutal, high-friction reality of 21st-century markets.

The 1952 Foundation: The Elegant Mirage

Harry Markowitz’s Portfolio Selection (1952) transformed finance from an art into a branch of mathematics. His core insight was that an investor should not maximize return, but rather Expected Utility, which balances the "mean" (return) against the "variance" (risk).

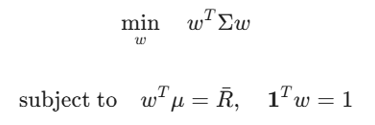

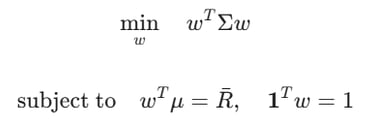

The Quadratic Framework

The standard Markowitz Optimization problem is defined as:

The Theory: By selecting assets with low or negative correlations, the term decreases faster than the weighted average of individual risks. This creates the Efficient Frontier.

The Anatomy of Fragility: Why MPT Fails in Practice

The 70 years following Markowitz have revealed that the theory is "fragile"—it works perfectly in simulations but often collapses in real markets.

1. The Estimation Error (The Optimizer as an "Error Maximizer") :

The most significant practical flaw is that µ and σ are unknown. We use historical data as proxies.

The Problem : Small errors in estimating µ lead to massive shifts in w.

The Result : The optimizer identifies assets that performed "too well" by chance and over-allocates to them. Instead of diversifying, the model concentrates wealth in the assets with the most positive estimation errors.

2. Correlation Breakdown (Endogenous Fragility) :

MPT assumes that σ is stable. However, correlation is not a constant; it is a state-dependent variable.

In Calm Markets: Assets move independently ( ρ ≈ 0).

In Crisis: Under liquidity stress, investors sell everything to cover margins. Correlations "gap up" to 1.0.

The Paradox: Diversification is a "fair-weather friend." It is present when you don't need it and vanishes exactly when you do.

3. The Gaussian Delusion (Kurtosis) :

Markowitz used variance as the sole measure of risk. This assumes returns follow a Normal Distribution (Bell Curve).

Real markets exhibit Fat Tails (Excess Kurtosis).

The Math: In a Normal Distribution, the probability of a "10-standard deviation" move is practically zero. In finance, these "Black Swans" occur frequently because market returns are governed by Power Laws, not Gaussian curves.

The 2024 Revision: Robustness via Convex Optimization

The paper Markowitz Portfolio Construction at Seventy (Boyd et al., 2024) provides the "2.0" version of this theory. It moves away from the search for a "perfect" portfolio and toward a "robust" one.

1. The Regularized Objective :

Boyd and his colleagues argue that we must "penalize" the optimizer to prevent it from making wild bets. They introduce Regularization Terms (Φ) :

L1 Regularization: Encourages sparsity and prevents "over-trading."

Holding Constraints: Explicitly limits how much of one sector or asset can be held, acknowledging that our estimates of are likely wrong.

2. Transaction Cost Integration

Classical MPT ignores the cost of getting to the optimal portfolio. Boyd’s 2024 model treats Transaction Costs as a primary risk factor. If the cost to rebalance to the "optimal" weights exceeds the marginal gain in variance reduction, the model stays put. This creates a "No-Trade Zone" that protects the investor from "churning" the account.

3. Factor-Based Covariance

Instead of calculating the covariance between 500 individual stocks (which creates a massive amount of "noise"), modern researchers use Factor Models:

F: Exposure to macro factors (Inflation, Growth, Momentum).

D: A diagonal matrix of idiosyncratic risk.This reduces the number of variables to estimate, making the model far more stable and less prone to "exploding" weights.

Conclusion: From Optimality to Resilience

The 1952 Markowitz model taught us how to dream of a perfect portfolio. The 2024 Boyd revision teaches us how to survive a real one.

Diversification does not always reduce risk. It only reduces risk if the optimizer is constrained by the reality of transaction costs, the instability of correlations, and the inherent uncertainty of our own data. Modern portfolio construction is no longer about finding the "Best" weights; it is about finding the weights that are "Least Wrong" across a thousand possible futures.

Contacts

blockainexus@gmail.com

main@blockainexus.com

Get in touch

Opening hours

Monday - Friday: 9:00 - 18:00